*Note: This post is very Euro-centric, because that’s what I know and that’s the viewpoint of most of my readers. Circumstances were/are different in other places, especially when we’re talking about living traditions, so while some of this can be extrapolated for those it’s not a one-size-fits-all thing. Keep that in mind when reading. I am also so not an expert with all of this, so if you find any mistakes please feel free to PM me and let me know!

“Antiquity” and “Modernity” are concepts at the core of quite a few debates in modern polytheism. That makes unwrapping them a great start to this “Concepts of Modern Polytheism” series!

To begin, I guess the first thing to understand is that Antiquity and Modernity don’t refer to time periods. That’s the obvious place our brains go, and where a lot of these discussions seem to founder, but it’s not strictly accurate. The distinction between the two is less about a timeline and more about worldviews.

What’s a worldview?

Essentially a worldview is the frame of reference we use when figuring out the relationships between aspects of our lives, ourselves, our relationships, and our world. It helps us put all of these things in their proper places and figure out what to do when things happen to disrupt that order.

All of us have a worldview, and it covers pretty much everything in our lives. It’s how we determine the difference between “good” and “bad” behaviors, between “right” and “wrong”. It’s how we recognize obligations we have to T/those around us, or that T/they have to us. It’s our worldview that shapes our sense of identity and provides the basis for how we figure out what fulfills and completes us.

It’s a big deal. And for the large majority of us all these determinations are made on a completely subconscious level.

That can be problematic, because every single worldview out there has inherent biases. Worldviews are biased by their very nature. When our worldview tells us something is good and something else is bad, that’s a value judgment being made right then and there. Not being aware of the biases in our own worldview means we could be making choices we’d never consciously make, simply because we’re not aware enough to know we’re making them.

How does that relate to polytheism?

When most people discuss polytheism they focus on the “multiple gods” part and pretty much drop the discussion there.

That’s incredibly simplistic, though. It changes the Power being recognized from one to many while completely missing the implications stemming from that change, and how those implications can change our worldviews. And that’s a shame, because if we’re ever going to truly restore or revive these ancient polytheistic traditions to something resembling what they once were we absolutely have to delve deeper. Those implications matter.

Since they’re so important we need to really understand them. That requires us to look at some world history, though. Stick with me through the end and it’ll all come together, I promise!

Antiquity

Let’s take our minds back to the time before monotheism became the dominant religious paradigm in the West. Specifically, let’s look at 30 BCE.

Europe, 30 BCE. Here we can see the Roman Empire before it took over the whole continent.

We can see from this map that the Roman Empire was in control of a huge chunk of territory, stretching through Europe, around the Mediterranean through the Near East, and into Egypt. That was quite a feat, especially considering that there were multiple cultures living peacefully under the Roman banner.

How did they do it?

We could talk about things like their excellent roads, or their standing armies, or their educational standards. And they all played their part. But one of the things that made the Roman Empire what it was is that government, religion, and morality were seen as distinctly separate things.

Wait… huh? How does that even work?

Pretty well, actually.

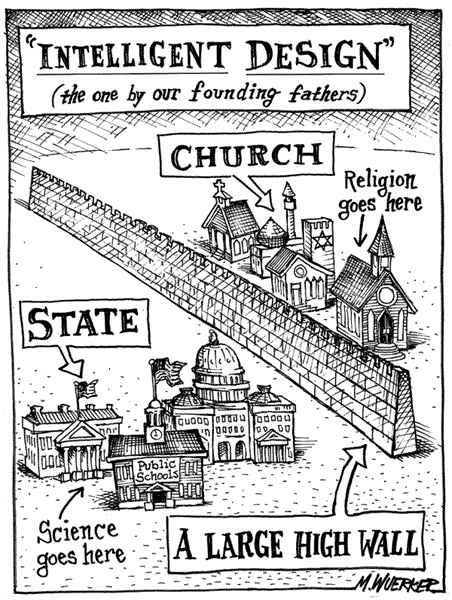

Here in the US we’re used to the idea of separating political and religious life. That’s the “Separation of Church and State” concept we’re all familiar with (even if those lines seem to blur with alarming regularity).

See, like this.

But separating religion and morality? For the most part that’s completely outside of our realm of experience.

For the Romans, though, it was the only way to go.

So let’s take each of those ideas individually, shall we?

Affairs of the State

Not every Roman was considered a citizen, and that was especially true of those new to Roman rule. However, if you were willing to play ball with Rome you could maybe become one. And that idea – that people could get a stake in the new system and even improve their status within it – became one of the most effective ways Rome ensured loyalty in the populace.

The rights and responsibilities of a Roman citizen varied depending on a multitude of factors, but at no point was religion or morality a part of the equation. Citizens didn’t have to honor specific gods, engage in (or refrain from) specific behaviors, any of that. They simply had to follow the law and not try to overthrow the government.

Classes of Roman citizens.

That being said, it was expected that citizens be involved in their government at whatever level they could. Rome had public assemblies, for instance, where people could state their views and vote, and citizens could run for public office. Financial contributions to the community were also expected of those with the means to make them.

Religious Life

Polytheism reigned supreme during this time period. There were literally hundreds of Powers openly honored within the borders of the Roman Empire alone, and absolutely no one was bothered by this. Why would they be? There was a core Roman pantheon, yeah, but the Romans operated under the idea of “the more the merrier”.

That made all kinds of practical sense, especially for an expanding Empire. Just accepting whatever Powers and spiritual traditions belonged to these new Roman citizens simplified their assimilation into Roman society enormously.

At the end of the day the Empire was much more concerned with consolidating military, economic, and political power than they were with enforcing some kind of homogeneous religious practice. That kind of thinking wasn’t even on the radar. There were some public rituals that everyone was required to attend, and they liked it if a local area added the official Roman Gods to their honoring/devotional practices, but for the most part they left local traditions completely intact.

The Roman Festivals of the Colosseum, by Pablo Salinas.

That was huge. Writing anything down wasn’t something the majority of these people did, and religious practices didn’t often get written about even when writing happened. Instead, these traditions were passed down orally and by demonstration. People didn’t read a book to figure out how to throw a festival, they did it the way their parents did it, and their parents before them. Religious rites and rituals existed in a lineage extending back hundreds if not thousands of years, and their relationships with the Powers they honored extended that far back too.

These were vibrant, living traditions. Some were more devout, some less. Some had intricate religious traditions, and some were rather simple by comparison. Regardless of the distinctions between them, though, the Roman Empire let them continue on as they always had. Hell, some of the most influential thinkers of the day opted out of polytheism entirely, claiming everything from pantheism to atheism, and that was ok too.

Morality and the Social Fabric

Because there were so many Powers honored across the breadth of the Empire, and because They were honored in so many different ways, Roman religion as a whole had no morality clauses (aside from some basic warnings against hubris and the like).

Local areas might have held their own behavioral standards, based on those living traditions mentioned earlier, and those of course changed depending on where you were. But for the Empire as a whole? Nada. There were no blanket taboos, no religiously-sourced rules everyone had to follow or else. There weren’t even widespread devotional requirements outside of the the aforementioned public events.

And really, how could there be? They had hundreds of different Powers who all had individual preferences and wanted different things from Their people. The Empire didn’t even try to regulate that.

The only interests the State had in personal morality were focused on community concerns, like outlawing murder and theft. As long as citizens participated in the public worship ceremonies – which had political and social components in addition to the religious ones – they were golden.

Individual behavior wasn’t mandated by the Gods or enforced by the State.

There was still a society to bind together, though, and a largely shared moral code is perhaps the strongest way to do that. So where did Roman morality come from if not religion?

Philosophy.

We study Roman philosophy to this day, and the Greek philosophy that came before it, because the philosophers were the ones asking and answering the questions we’re now used to priests covering. Not “why are there seasons” or “why was the world made” – those questions were answered by myths, just like they were/are in almost every culture up to the modern era. They focused instead on questions of more direct utility, like “what qualities are possessed by an upright person” and “what makes a good life”.

Zeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy. He was Greek, but his philosophy was hugely influential in Rome too. He was a pantheist.

Roman morality – or, if you want to get technical, the Roman ethical system – was rational, not religious. There were a handful of philosophical schools that dominated Roman society, and it’s with those philosophical stances that the social fabric was maintained.

Those three aspects of ancient Roman life – good citizenship, religious freedom with living traditions to draw on, and a philosophically-based morality – were balanced against each other, with each one being seen as important. Together they make up the Antiquity worldview.

Transition

I didn’t pick 30 BCE out of a hat when I chose the map pictured at the beginning of all of this. That’s around the same time that Rome took over a little province called Judea, in what we now consider Israel/Palestine.

That’s also when we get the first seeds of the Modernity worldview.

Judea

In the sea of Antiquity Rome Judea stuck out like a sore thumb.

Here’s a close-up. The city of Jerusalem is just above and a little to the right of the “Judaea” label.

And it wasn’t even because the Jews who lived there were monotheists. It was odd for Rome, sure, but it really wasn’t a deal. Monotheism was considered just one more religious weirdness encountered by the Empire as it expanded. Remember, Rome had everything from devout polytheists to strict atheists within its borders. Monotheists were just another thing.

In fact, before everything went to hell in 66 CE Rome treated the Jews like they treated everyone else. Even more tolerantly in some ways. Not only did they not try to force the Jews to honor any additional Gods, they gave the Jews a pass on religious observances required in other cities. The Jews actually burned offerings in the Temple of Jerusalem for the Emperor of Rome in appreciation of his tolerance!

Monotheism in and of itself wasn’t the problem. It was all the stuff stemming from monotheism that started to gum up the works.

The Romans separated governance, religion, and morality, right? They pretty much had to, considering the number of Powers and perspectives within their borders. And it’s that separation that allowed them to so easily accept the Jewish monotheism.

The Jews didn’t separate those things, though. They couldn’t. For the Jews those three concepts were inextricably linked, with both governance and morality stemming from and supporting their religion. Not only that, but all of those things were codified in written records maintained by the Temple and faithfully followed to the letter, with no room for deviation and precious little room for growth.

One of the biggest problem areas was that the Romans and the Jews had completely different ideas about the role of the State. For the Romans the government was all about working towards the common good, with freedom for political activity within that. The Jews saw the law as the enforcement arm of their God more than anything else.

Pilate washing his hands – a kind of spiritual cleansing – after the Jewish crowd voted to crucify Jesus. An example of Jews using the law for religious purposes, and how uncomfortable the Romans were with that perspective.

The Jews, because of their religiously-backed morality code, were almost required to live in separate enclaves from the Romans around them. Not because the Romans required it, but because the Jews did. Their distinct culture made them incredibly insular.

That did not endear them to their neighbors. It also completely prevented them from assimilating into larger Roman culture. The well-oiled machine that was “expansion of the Roman Empire” had no avenues to work with when it came to the Jews.

Add in the fact that the Emperor claimed divine lineage, which the Jews didn’t accept, and you had a tenuous situation. The cessation of honoring the Emperor at the Temple of Jerusalem in 66 CE was just more fuel for the fire.

Of course, that’s also when war broke out and the Romans burned the Temple of Jerusalem to the ground. Whatever small chance there had been for Jewish assimilation into the Roman Empire died along with the flames.

The Burning of the Temple of Jerusalem.

Judaism provided the seeds for the Modernity worldview, but it was a Roman Emperor that planted it and another religion entirely that helped it sprout.

Conversion

Christianity was a splinter sect of Judaism with pretty inauspicious beginnings. Between the crucifixion of Jesus around 33 CE and 312 CE it was mostly an underground sect. The direct opposition of Christians to the values held by Antiquity Rome made them seem dangerous to the unity of the Empire and, unlike most other religions they encountered, the Romans actively persecuted them because of it.

Then, in 312 CE, Emperor Constantine turned his back on Rome’s long polytheistic history and state religion and converted to Christianity.

Constantine’s conversion changed things. Drastically. Christianity likely wouldn’t have amounted to much of anything without powerful support, but with the Empire behind it Christianity was given teeth and considered a unifying force.

That is what birthed the Modernity worldview.

Modernity

Remember me saying that when the Roman Empire of Antiquity conquered a new area, they enforced governmental authority but not religious authority? That they left that to the people? And that the people were free to live their lives by whatever moral code they chose, separate of their faith?

Yeah, Modernity tossed that attitude out the window.

Instead of the careful separation of the Antiquity worldview, Modernity followed the Jewish and later Christian pattern by knotting all those elements together.

We’ll even call it a Gordian Knot, a la Alexander the Great. I’m so funny. 🙂

The government and the moral code both came from and supported the Christian faith, which was of paramount importance.

Obviously, of course, monotheism accepts belief in only one God. That might not have been a problem on its own, but knotting everything together led to the idea that the Christian Emperor drew his authority from that one God. He was Emperor only because the one God said he was.

Because of that, acknowledging other Powers or standing against the Emperor was seen as a challenge to both the Church and the State, since they were both considered facets of the same thing.

That logic carried over into personal behavior, too. Not behaving in accordance with Biblically-based morality rules equaled rebellion against God, which equaled rebellion against the State. Acting in an immoral fashion became not a philosophical matter but the breaking of a religious mandate and a challenge to the authority of the Emperor.

In many ways the changing moral landscape was the most subversive part of all this. True belief and devotion are impossible to police, and treasonous intent can be difficult to prove without a weapon in-hand, but behavior? That’s always on display. It’s how you’re judged by your peers. And at a time when a good reputation really could mean the difference between life and death, acting in a morally upright way (as defined by these new rules) became a matter of basic survival.

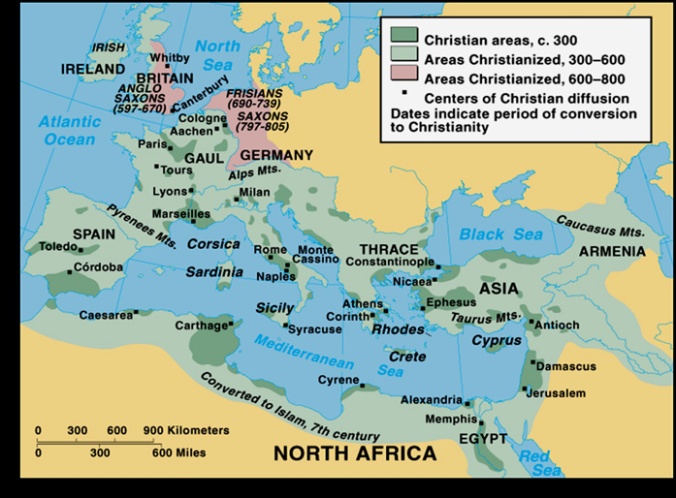

All of this didn’t just apply within the Empire’s borders, either. Expansion, once fueled by a desire for military and economic dominance, became a matter of spiritual dominance as well. And as the Empire spread, so too did Christianity.

It didn’t happen all at once. It was a gradual thing.

All Roman citizens were required to turn away from the hundreds of Powers they had previously honored and follow only the Christian god. All newly conquered peoples were required to become Christian too, and those who resisted were converted on threat of execution.

Those who did convert, however, were granted privileges by the conquerors that stubbornly polytheistic people were not.

A concept mastered during early conversions.

The peasants out in the fields, most closely tied to the land and outside of direct Roman supervision, were able to hold on to aspects of their original religions the longest. Eventually, though, they too converted and their polytheistic traditions were lost.

By around 800 CE the Modernity worldview was fully realized in Europe. And it dominates the West to this day.

Bringin’ it Home

Monolithic Christianity has taken some blows since then, no question. More and more people are leaving the Christian faith every day, and many of those who claim Christianity as their faith are not devout. Progressive Christianity is on the scene now, too, providing room for more tolerance within the faith. Overall we’re slowly growing more accustomed to separating out politics from religion, despite occasional regressions and setbacks.

While all of these things are helping us moderate the worst effects of Modernity, the worldview itself is still going strong. And no matter how self-aware we think we are, Modernity is so embedded in our culture that it’s hard to see it unless we start looking for it.

But once we do? Boy howdy. We can see it all around us.

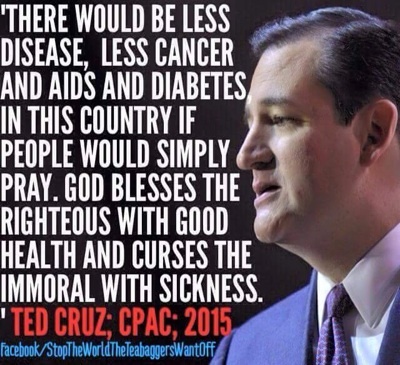

It’s in our political processes, when the faith followed by a political candidate becomes a pivotal point of their campaign.

It’s in our society, when behavior is judged by religious standards.

And it’s in evangelical Christian churches across the country, when anyone and everything not falling within Christian guidelines is blasted as being demon-spawn.

It’s not just Christians doing it, either. We get more of that here, but terrorists overseas are using the exact same logic – albeit in a different Power’s name – to do the exact same thing.

It doesn’t have to be that way, though.

Choosing Our Worldview

And that brings us to why this whole Antiquity vs. Modernity discussion even matters.

Like I said earlier, we all have a worldview. As products of the modern age we all received the Modernity worldview by default. Once we start grappling with these ideas, though, once we start seeing how far apart the Antiquity and Modernity worldviews are, we can no longer claim ignorance. We have to/get to make a conscious choice about which worldview we want to use, every day, and we have to live with the consequences of that choice.

We can of course choose to keep using the Modernity worldview we’ve already got. It’s easy, and comfortable, and requires very little work from us to maintain. It’s also the worldview used by our culture at large, and sharing it helps us better relate to the people around us. However, choosing this road means we’re accepting that our polytheism, however it manifests and however fulfilling we may find it, will never balance out in a way similar to the balance maintained by those who trod this path before us.

Some of us are perfectly ok with that. It works, right? Some of us aren’t, though, and want another option.

Choosing to switch to the Antiquity worldview is the harder choice. It requires a self-awareness that can be both challenging and exhausting. The Modernity worldview is so engrained in our psyches that the effort required to root it out is constant. We have to pick apart the political/religious/moral knot in our heads at every opportunity, painstakingly separating those threads out into something we can use to support a new paradigm. It also requires study and contemplation, because unlike those who came before us we modern polytheists don’t have living traditions on which to draw (unless you do, in which case carry on). It also puts us out-of-step with the people around us who still use the Modernity worldview, which can be both frustrating and isolating.

In exchange for all our hard work, however, we get to live with a perspective that’s much closer to one the Powers with which we work recognize, and one that’s closer to the one held by polytheists before the rise of Modernity.

Whichever way you choose, choose with intent.

Thank you for going through and doing the hard work of identifying Antiquity, Modernity, when they occurred, where they came from, how they came about, their effects, and the general positions on them. Would you mind if I linked folks to this, either personally or through my blog when we need a reference point?

Not at all! Please feel free to share this around. I’m glad people might find it helpful!

Reblogged this on Strip Me Back To The Bone and commented:

People are writing all of the things!

I really appreciate this article of Caer’s. I’ll admit, this is the first time I considered modernity and antiquity as worldview concepts, rather than time-frame concepts, and this consideration adds further nuance to the discussions regarding the draw-backs of modernity.

While I may not agree with the conclusions that an individual might make regarding modernity (I’m not sure yet, I’m still chewing on the idea), I do appreciate and whole-heartedly support the idea that we need to be aware of our biases and our worldviews, that we need to question, that going along unconsciously is a habit that we ought to challenge. Could be that, after questioning and challenging how we see the world, how we see our societies, how we see ‘modernity’ may bring us back to a place where we started from when we began questioning, but at least it would be a conscious decision, which is, to my mind at least, preferable.

“Could be that, after questioning and challenging how we see the world, how we see our societies, how we see ‘modernity’ may bring us back to a place where we started from when we began questioning, but at least it would be a conscious decision, which is, to my mind at least, preferable.”

I absolutely agree with this sentiment. If I’m going to do something I want to do it on purpose! I’m glad you’ve found this post helpful!

Actually the Romans didn’t really separate government from religion. The two were very much intertwined in both the Republic and the Empire, but not perhaps in a way that we would expect. it didn’t lead to the type of fundamentalism or theocracy that we might expect were we talking monotheism. They did, however, have a state religion and rites and rituals done within its boundaries were seen as necessary for the integrity and strength of the state as a whole. Likewise emperor cultus. one looked to philosophy for one’s moral code though, you’re right about that. it’s funny, I teach a course in Myth and Literature in the Greco-Roman world and i think it’s a bit shock for some of my students when I point out that ancient polytheists didn’t get their morality from their religion. lol.

Yeah, there was definitely some overlap between government and religion in Rome (like the required public rituals, and the Emperors claiming divine lineage), but that avoidance of fundamentalism was more the point I was trying to make. I left out a lot of detail in an attempt to simplify things.

I’m glad you commented! Writing this all out actually reminded me of a point you’ve made in several blog posts!

You’re a staunch supporter of the Antiquity worldview. From that perspective social justice activities are not devotional in nature. They’re the right thing for us to do as human beings, and maybe even as good citizens, but that has nothing to do with honoring the Powers because they’re completely separate things. Devotional activities are for the Powers alone.

For those using the Modernity worldview, though, that distinction isn’t being made. For them social justice activities are of course acts of devotion, because morality stems directly from the Powers. Morality and religion reinforce and inform each other, so social justice work and devotional work naturally blend together.

That’s why I’m so excited to see people engaging in these Antiquity vs. Modernity debates. It isn’t just a theoretical distinction – there are real world implications here that need to be considered.

More than overlap actually. the two were integrally intertwined but not in a way, I think, that we would expect coming from the US where IF we had religion anymore intertwined with our government, we’d have a dominionist theocracy! Polytheism never worked like that. But Roman government was almost an expression of pietas, at least from the roman perspective.

I think that one of the criticism i have of the modern world view is the emphasis on social justice INSTEAD of devotion. it’s easy. we get our pats on the head. we can feel as though we’ve made a difference even though we haven’t done more than a twitter post, etc. But it’s not devotion. I wonder how active some of these social justice proponents would be if they had a direct engagement with their Gods that did NOT support politics they already held. and that is my criticism. i frankly think people default to social justice because they can feel good about themselves and it’s much, much easier than devotion (not that it doesn’t need to be done, mind you). and I think that regardless of what is being said, social justice isn’t actually devotion. especially not when any other expression of piety is lacking. One may be inspired to social justice work out of one’s piety and devotion but the two are apples and oranges. It’s just one more way of putting humanity above the Gods. When social justice and devotion blend, devotion always seems to get slighted.

That being said, i can’t say that my engagement in charity and social justice (Which I will never blog about) isn’t informed by my polytheism. It is. Just as for the Roman there was no pietas without civitas I think that there is no being an engaged, awake, aware polytheist without a willingness to try to shape the world into something a little more amenable to actual polytheism.

The problem i think with allowing one’s religion to inform one’s morality unquestioningly is that it is just that: unquestioned. and that leads to a reification of one’s moral precepts over anything the Gods might *actually* be trying to tell you. Religion was never about morality in the ancient world, or rarely so; it was about engaging well with the Gods. If we need religion to teach us to engage well with humans, maybe we better rethink our humanity.

There is the idea of social justice that has perpetuated with the explosion on the internet, and there are the religions that embrace social justice as a key concept and as a devotional measure that the divinities expect their devotees to engage in if they are in right relationship to them. There is a difference between posting on the internet and doing the work that leaves you sad, broke, and at loose ends because you cannot change the world for those who are the people of your divinities. It doesn’t feel good to watch people die because help can’t be delivered, and to go back to that day after day after day because you love your divinities and that is the world the religion does–to even the playing field for those that suffer. That is the devotion people get asked for, and it is anything but easy.

It may be separate for you and your beliefs, and you may not count it as devotion, but there are quite a few religions that do count that, and do demand it. Every living indigenous religion survives because they were founded on social justice based in love and devotion for the divinities there. The whole religion over hundreds of years hearing it wrong? Nope.

I also think we have to be careful in speaking of ancient Roman religion, indeed any polytheism in the ancient world in generalities. Rome had a state religion which was deeply and inextricably intertwined with its government in a way that I think is difficult for us moderns to comprehend cleanly. But there were also thousands of cultus of different Gods, and there was the influx of various foreign cultus too, and those cultus were not having the role in government that the state religion did. (save that often those foreign cultus were brought in by the state and were under state supervision. it’s much messier than I think we expect).

most of those religions that count is specifically as devotion are very monotheistic. I’ve explored this in length on my blog and i’m not going to repeat myself here, especially not for you.

It doesn’t feel good to watch your people, or any people for that matter suffer and nowhere have i said that one should not get involved. I think social justice is crucial to our world especially today. But there is a difference between that and devotion. Yes, love of the Gods may be the thing that gets a person out there doing something but I rather think that’s a component of being awake. I don’t even particularly have a problem with someone doing justice work X as a devotion to Deity X. What i will always object to however, is when social justice work becomes religion. no, no, and no.

Pingback: Broken Lines | Sarenth Odinsson's Blog

Reblogged this on Ironwood Witch.

Pingback: Which “Modernity” Do We Mean? | The Lefthander's Path